The Challenges of Safety in Sport Implementation

Offering youth or coached programming is common in climbing gyms. Whether geared toward competition or recreational options like birthday parties, these programs are still sport programs at their core.

SafeSport training and implementation may be needed in any or all of these types of programs, at least to a degree.

Article At A Glance |

|

Training requirements for programs related to the competitive pathway would fall under the requirements outlined by USA Climbing or CEC Safe Sport policies and resources. This information was discussed in a previous article.

What about the other programs and offerings?

Summer camp staff require more training. Local state and provincial law often outlines what type of training and licensing camps and camp staff should have.

For example, in Canada, camp staff initially were introduced to the High Five Program, a non-profit founded by the Ontario Parks and Recreation Department. High Five has design guidelines and principles for ensuring a positive recreation and sport experience for participants. All camp staff also needed to have first aid and CPR training, complete a background check, including a vulnerable sector check.

Now, concussion training has been added to the requirements. All this training was in addition to the risk management training of instructing and monitoring climbing activities. The cost invested in staff continued to grow as well. The training time, the fees to the certifying bodies and organizations impacted the cost of delivery, not to mention the cost to coordinate and administer all this staff training.

For climbing facilities offering day camps or camps for only a few weeks, the facility may not see the investment as worth all the challenges to ensure everyone is trained. Limited interaction between campers and staff does mean there could be less risk of a negative experience occurring.

Sign Up For Our Webinar on Safe Sport This Thursday!

A second factor determining whether training is appropriate is an owner or operator's risk tolerance. Some climbing facilities, like universities and municipal recreation centers, tend to be very strict in what they allow.

The amount of contact time between the campers and the instructors is higher, and responsibilities can be more familial in nature, like making sure they eat lunch. This closer relationship could be considered a higher likelihood for something untoward to occur.

A coach relationship with a high-performing athlete who trains more frequently and is challenged in effort can be considered a more emotionally dependent relationship than the recreational approach to a once-a-week climbing opportunity.

While both carry risk, the likelihood of an incident may impact the risk assessment and, therefore, the intervention strategies.

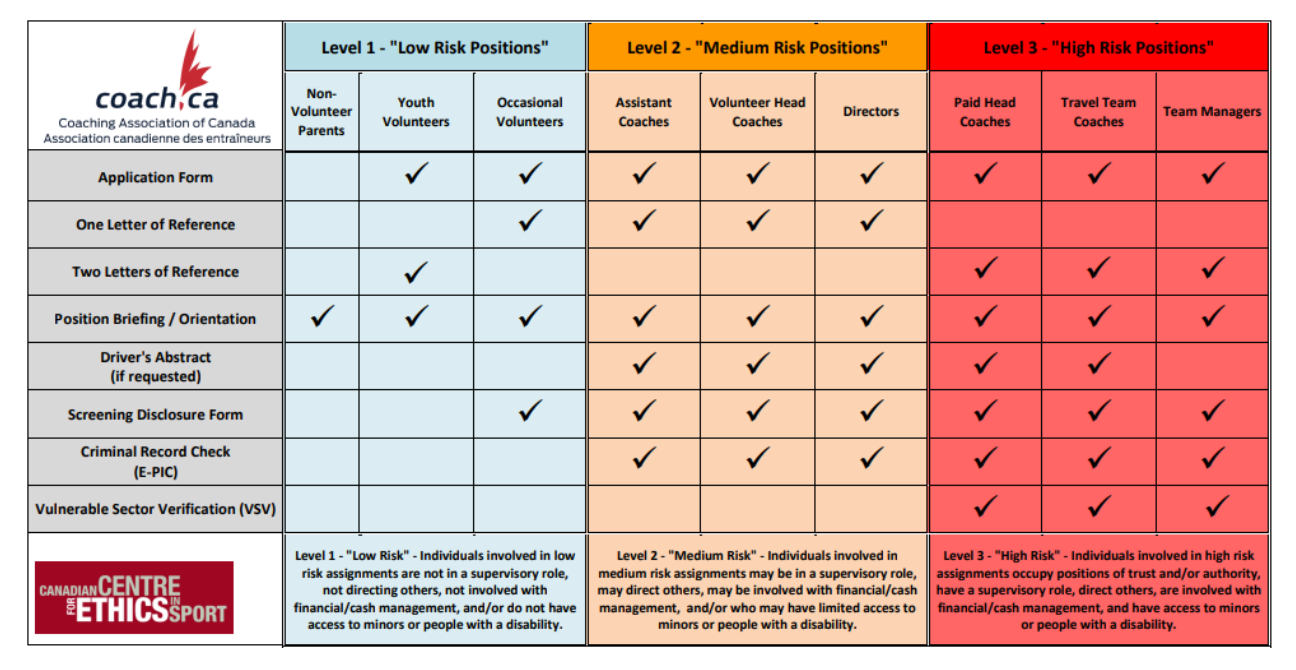

Background checks and vulnerable sector checks tend to be common. The Canadian Sport governing body recommends the following in their Background Screening Policy Manual:

Some sport organizations will cover the costs of background checks, especially in the case of volunteers or paid employees. And the CWA offers discounted background checks for members. The price can vary from location to location, and the extent of the check is determined by the nature of the background check one employs. In Nova Scotia, for example, the Vulnerable Sector check has no fee, whereas the criminal record check does have a fee associated with it.

The challenge for everyone is that no two individuals experience the same coaching session in the same way. Each participant experiences the actions and words of a coach through their own lens of expectations, past experiences, and sensitivities.

A coach can offer what they believe is a reasonable, well-intentioned practice only to hear that it potentially threatens the mental and emotional well-being of an athlete. That same practice could be considered the best practice ever by another athlete.

In other words, a code of conduct agreement offered to participants and parents or guardians (as well as coaches) should be in place for programs. This document can be drafted to stipulate the expectations for the coach, the participants, and the parents to ensure as many potential conflicts as possible are addressed before the program begins. This document can be helpful in camps and ongoing high-performance programs, with adult or youth participants.

Now consider that most coaches receive very little training and preparation before they begin working with the participants they coach. How the heck could this new coach possibly know what is appropriate and how to protect themselves as a coach in that situation?

Based on the Long Term Athlete Development model and matrix developed by Climbing Escalade Canada, there are some guidelines that may fit the general population. Coaching on a group level should be as much about enjoyment and slow development in skill and strength, not an escalated approach, as one may expect at the high-performance or personalized level.

Just like any physician, the goal should be to do no harm.

At a high-performance level of coaching, an athlete should have a very personalized and specialized plan based on their various areas of weakness identified through a needs assessment and the goals the athlete has for their performance. The coach would factor in the amount of time the person has available for training, any limitations on access to training, and then provide some reasonable objectives or mini-goals the athlete could work toward over the course of multiple months. This requires specialized knowledge and training in the arena of applied anatomy, physiology, technical movement, and sport psychology.

Whether coaching a recreational youth or competitive adult climbing team, the coach needs training in movement skills, terminology, risk management, and competition rules. Many would argue that a coach should have first aid training and, if working with youth, Safe Sport training.

Instructors and coaches assume a lot of risk and responsibility when they take the role.

Only a select number of things any coach or instructor can confront on a day-to-day basis:

- An angry parent who wants to know how their child managed to sprain their ankle

- The youth who defies instructions and pushes back on the coach’s practice instructions

- Always needing to protect oneself under the rule of two

- The risk management of a six or eight to one ratio

- The responsibility for awareness of potential eating disorders

- The possibility of abuse or harassment from other teammates or coaches

That’s a lot of responsibility.

The Potential

The CWA is pleased to announce an effort to develop resources to support climbing facilities in navigating the risks unique to coaching programs, training staff to work with participants, and align with the core values of the guidelines.

If you have ideas you wish to share, email coachandtrainingcommittee@cwapro.org

About The Author

Heather Reynolds is a licensed kinesiologist, High Five Trainer (Sport, PCHD), CEC Climbing Coach, CWA Climbing Wall Instructor Certification Provider Trainer. She works as a Consultant to the CWA. She blends her knowledge of movement, physiology, and education to develop a multitude of successful climbing programs designed to support and engage youth. Having worked with youth for over 30 years as a recreation instructor, leader and educator, Heather supports the values and expertise available in the High Five Program, bringing quality assurance to youth-based sport and recreation programming.

Heather Reynolds is a licensed kinesiologist, High Five Trainer (Sport, PCHD), CEC Climbing Coach, CWA Climbing Wall Instructor Certification Provider Trainer. She works as a Consultant to the CWA. She blends her knowledge of movement, physiology, and education to develop a multitude of successful climbing programs designed to support and engage youth. Having worked with youth for over 30 years as a recreation instructor, leader and educator, Heather supports the values and expertise available in the High Five Program, bringing quality assurance to youth-based sport and recreation programming.